Surprising Stories: The Buttes-Chaumont: A Model for a Green City

Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. Phil Beard / Flickr

As we leave our homes after two months of lockdown in Paris, our Surprising Story this week visits the Buttes-Chaumont, one of the city’s first public parks and urban renewal projects. Part of Baron Haussmann’s mid-19th century designs for modernized Paris, we’ll see how one of the most noxious places in Paris became one of its most picturesque.

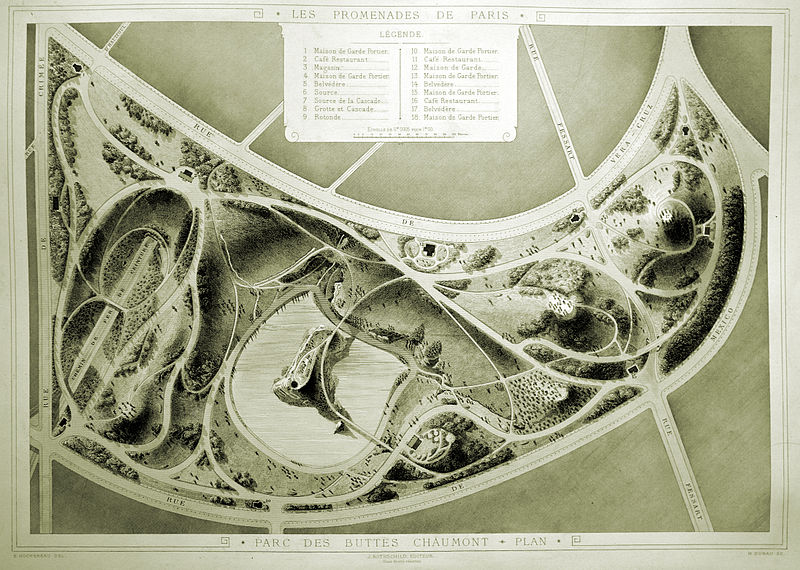

Plate of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, Paris, France. from the book: Alphand, Adolphe: Les Promenades de Paris. Paris 1867-1873. / CC

In his Memoirs, Baron Eugène Haussmann, who served as Naploéon III’s powerful urban planner, recorded that the Emperor wanted to create public parks and squares so that ‘workers, families, and children’ could improve their health, and enjoy gardens for leisure activities. To achieve this, from 1856-1870 Haussmann created a ‘green plan’ within the recently expanded city limits that included four large public parks and dozens of squares and planted promenades. Among these, his most celebrated renewal project was the Buttes-Chaumont, a 62-acre park, located in the 19th arrondissement.

The Buttes-Chaumont, or bald hill (chauve-mont) was one of the most nefarious sites in the city. From the 13th to 18th centuries it was the designated spot for the public hangings of criminals. Deserted after 1760, it then served as a sewage dump for the city and the open air cesspools were notoriously repugnant with malodorous smells. The engineer and landscape architect for the project, J.C A. Alphand, recognized that the dangerous emanations spread from the site across the entire city. Deep underneath this landscape was a gypsum quarry. Haussmann’s contemporaneous construction of modern apartment buildings (known today as Haussmannian buildings) had virtually exhausted the quarry, which produced the plaster and lime so essential to the building trade.

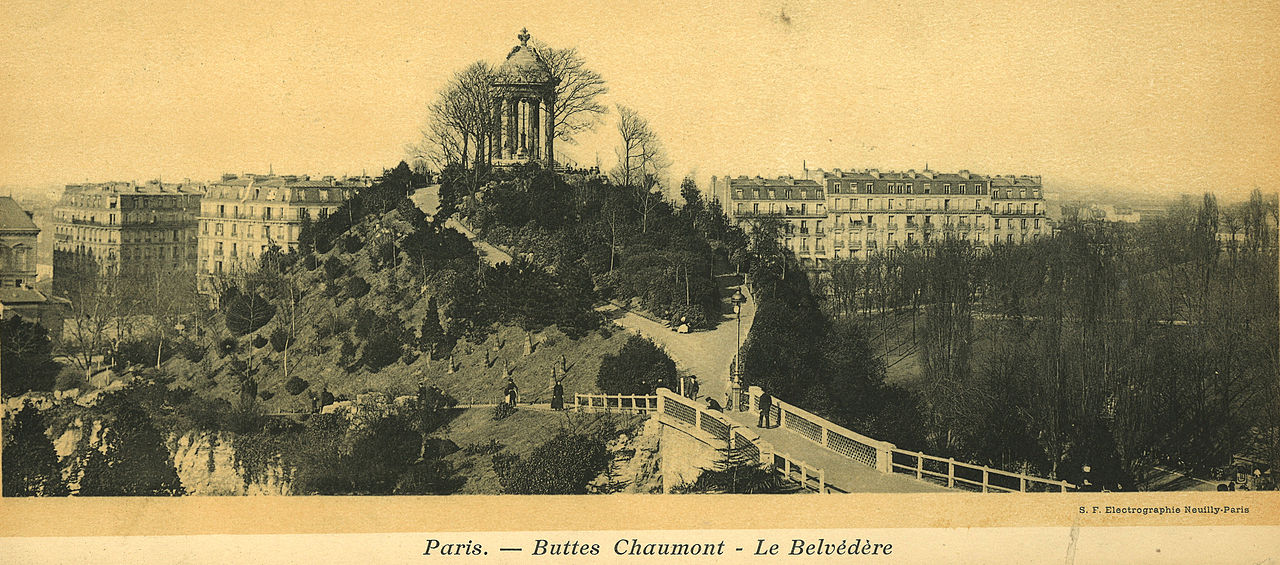

S.F. Electrographie turn of the century photo / CC

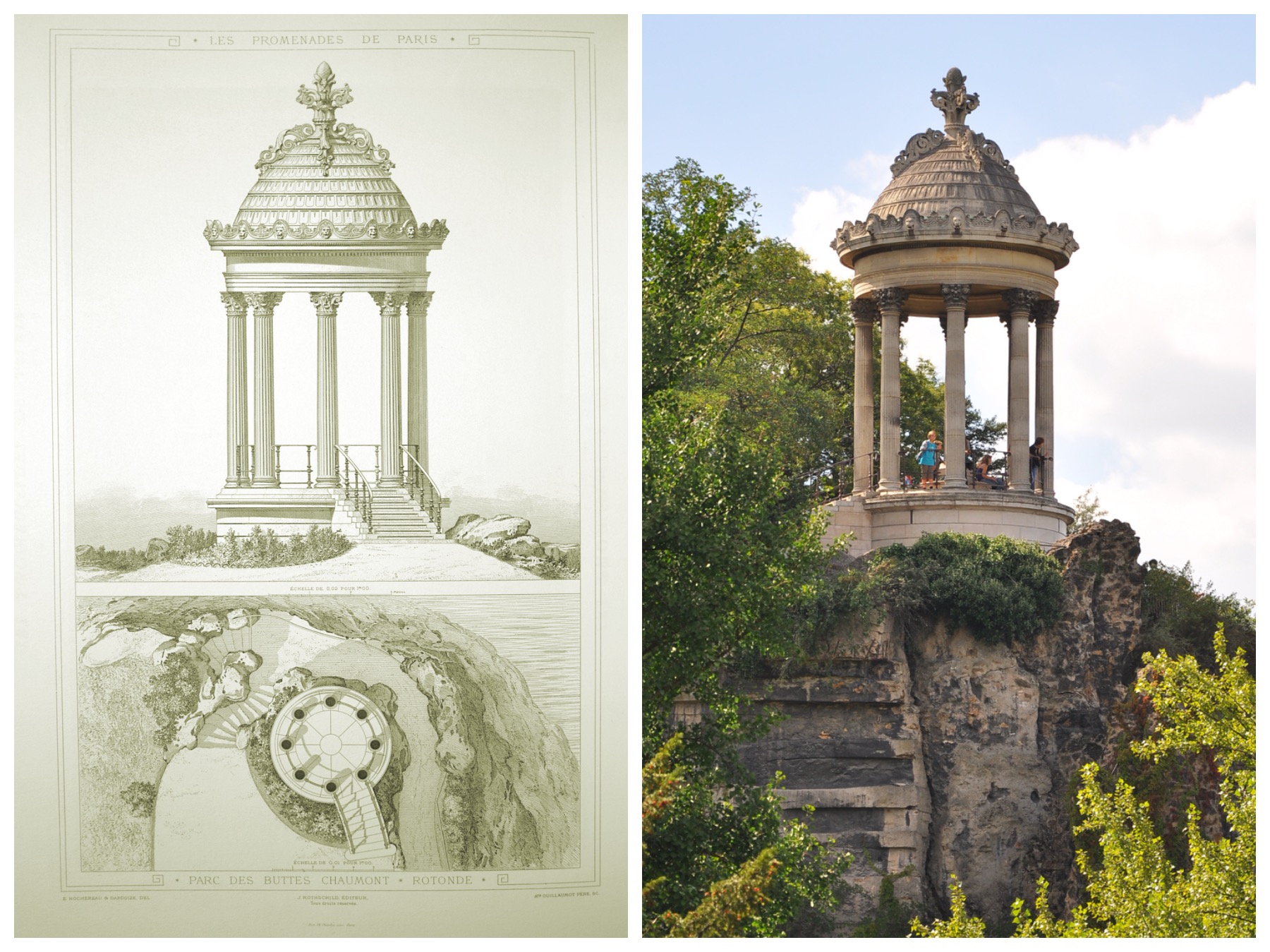

Alphard’s crescent shaped plan reveals how he transformed the disfigured landscape into a dramatic picturesque park. Alphand dynamited the remains of the quarry and modelled the blasted stone into a centerpiece of rock that soars fifty meters high above an artificial lake and is crowned with a belvedere temple. The lake was lined with a relatively new material, béton armée concrete, which Alphand used in several ways in the park. He blended concrete with the existing stone to create a dramatic waterfall within the former quarry (with fake stalagmites) and channeled the cascading water into concrete-lined rivulets which meander throughout the park. Alphand built a railroad track to bring in two hundred thousand cubic meters of soil to make the ‘chave mont’ fertile. Traces of former railroad were integrated to the final design.

To access the belvedere temple, a 63-meter-long suspension bridge was commissioned by none other than Gustave Eiffel. Hanging eight meters above the lake, the bridge afforded visitors’ views over the lake as they ascended to top where they stand underneath a copy of Temple of the Sybil, by the architect Gabriel Davioud, and enjoyed expansive views over the whole park and the north of Paris.

Alphand also planned curvilinear paths to connect the different parts of the garden: the perimeter was outlined with wide carriageways and narrower paths were designed for promenading. Alphand turned to the landscape architect Barillet DesChamps to plant the garden with exceptional trees and flowers, such as Lebanon cedars, Gingkos, and a Giant Sequoia.

Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. Yannis Sommera / Unsplash

The Buttes-Chaumont today is an oasis of green appreciated by joggers and gastronomes alike. Alphand’s plan included four restaurants and cafes spread around the park, suggesting that nineteenth visitors would have a leisurely afternoon strolling, visiting the cafés and appreciating the views. Restaurateurs have re-invested the park, with popular establishments like Rosa Bonheur, named for the celebrated painter.

For the flaneurs of yesterday and today, the garden is a magnificent example of landscape architecture for urban renewal: Alphand integrated then industrial industries—cement, iron, and acclimatization of plants—to transform urban blight into a healthy, green space, a model that continues to inspire the greening of Paris at the nearby La Villette or Promenade Plantée.

You can learn more about this innovative park on our stroll combining the Buttes-Chaumont with La Villette. Our tours, using Paris as an open-air textbook, are perfectly designed for exploring the city with safe social distancing. More details on this tour and our other experiences of Parisian gardens here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!